August 31, 1832

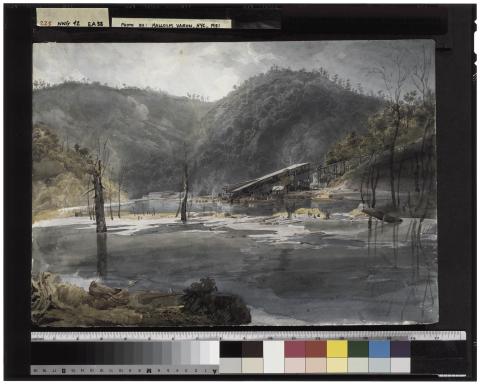

31 August: At eight o’clock our entire group of companions at the inn set out to seek the objects of interest at Mauch Chunk. Only the smallest part of the town is located  in the Lecha Valley, where our inn is the last building on the way down. The largest section is built in a narrow street of small wooden houses extending for about a mile into the lateral valley from which Mauch Chunk Creek emerges and joins the Lecha. Here live the various workers, day laborers, and other persons, some [Page 1:85] of them employed at the mines. This whole town [has] developed since the local coal deposits, located 9 miles from here on the top of the mountain, began to be worked.

in the Lecha Valley, where our inn is the last building on the way down. The largest section is built in a narrow street of small wooden houses extending for about a mile into the lateral valley from which Mauch Chunk Creek emerges and joins the Lecha. Here live the various workers, day laborers, and other persons, some [Page 1:85] of them employed at the mines. This whole town [has] developed since the local coal deposits, located 9 miles from here on the top of the mountain, began to be worked.

Because coal removal at that elevation was difficult, a railroad was built down to Mauch Chunk. On this railroad fifteen coal wagons are always fastened together. Controlled by a driver, they coast down and then are pulled up again by mules. Such trains of fifteen cars are always combined into groups of three, that is, forty-five cars at significant intervals. Behind these three groups of cars always comes a unit of seven other cars, joined to one another, also controlled by just one man; in every one of them, there are always four mules. These mules descend as rapidly as the coal does; when the coal cars are emptied, they are hitched up to pull them back up again. This is done five times a day. The 9-mile-long railroad consists of parallel wooden ties on which the iron rails are fastened. There is only one disadvantage here: in order to limit costs, a single track was laid so that ascending and descending cars must use one and the same track, as a result of which an accident can easily occur. In order to lay a double track—one for ascending and the other for descending coal cars—one would have to remove another wide section of the mountain face, since the road is cut into the high mountain wall, and this would greatly increase costs. At several wide spots where the area permits this, turnouts have been constructed. Double tracks are found there.

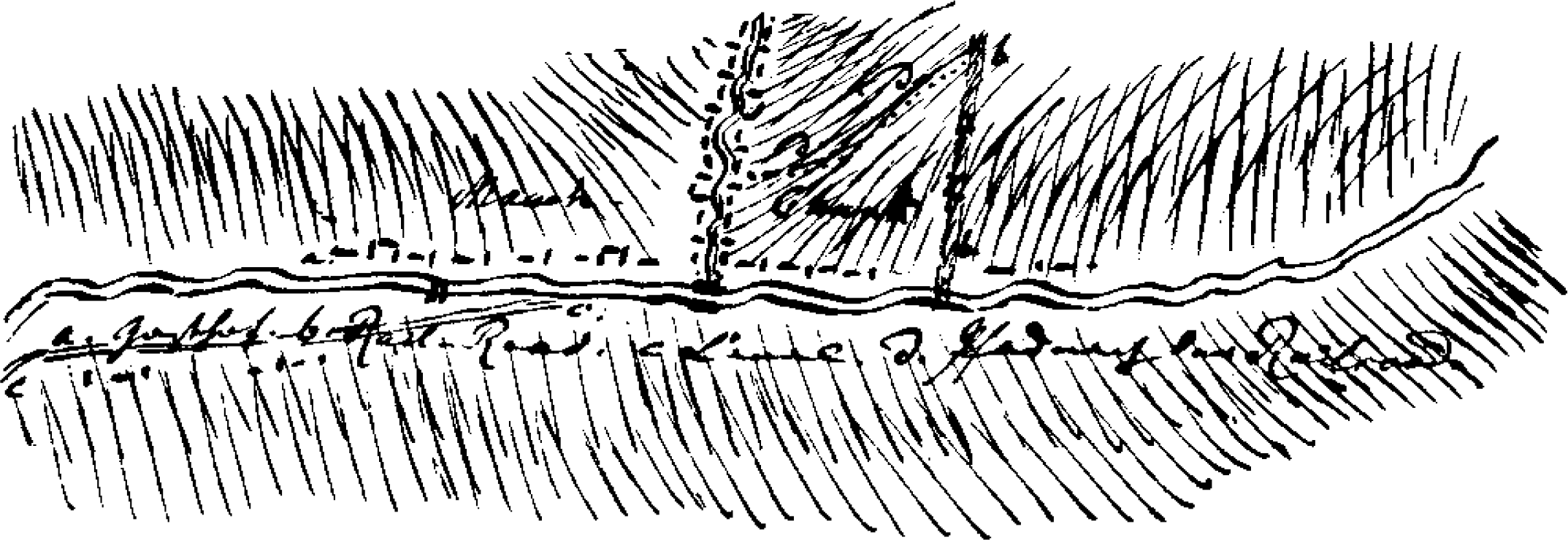

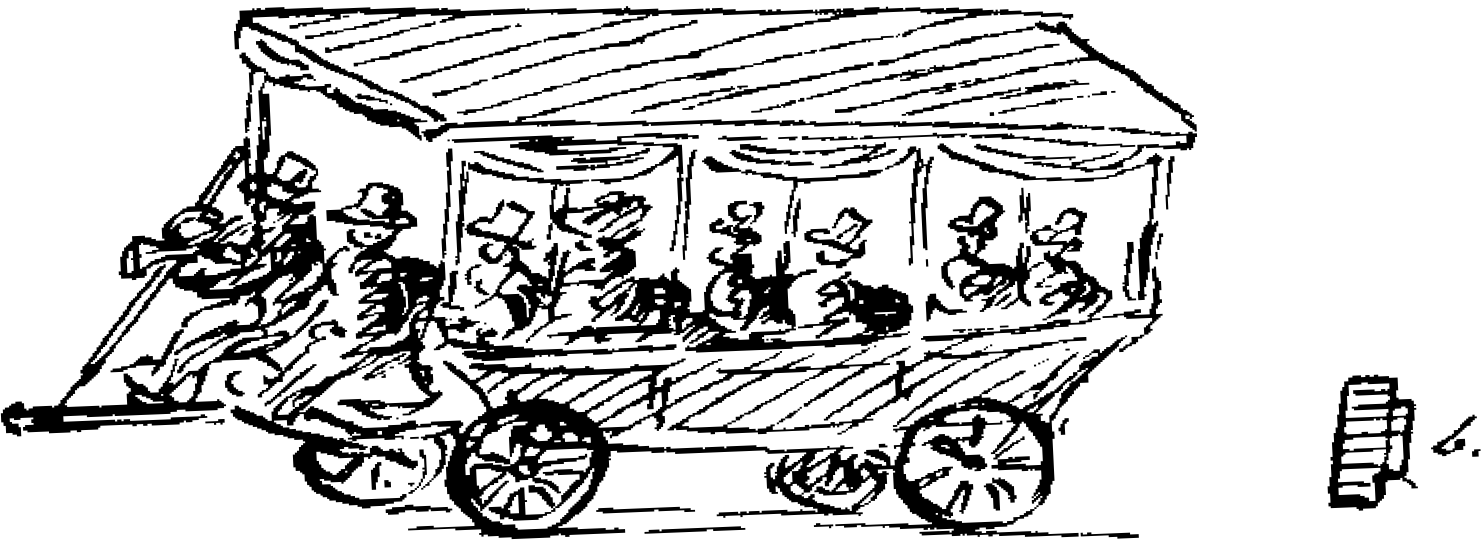

From the Mauch Chunk Creek valley, we climbed the steep path ‘d’ [see fig. 3.8] in great heat and found the railroad stages standing in readiness there on the  track about 150 feet above the town. These are light, four-wheel carriages with eight seats, open at the sides where poles support a roof. They have small iron wheels with a flange, by means of which they run on the track or rails, as indicated by ‘b’ [see fig. 3.10]. The coachman (driver) sits up front on the right and has

track about 150 feet above the town. These are light, four-wheel carriages with eight seats, open at the sides where poles support a roof. They have small iron wheels with a flange, by means of which they run on the track or rails, as indicated by ‘b’ [see fig. 3.10]. The coachman (driver) sits up front on the right and has  a horn (post horn), in order to give signals. With his other hand he grips a rod. As soon as he pulls back on it, the rod firmly presses a certain wooden device against the wheel, whereby the friction becomes so strong that the wagon is first slowed down and finally, if so desired, brought to a stop. Since the coal cars, expected at any moment from the mines, could not be long in arriving, we had to wait half an hour longer, for one must avoid meeting them on the track, and one always knows the times when the track is free. We sat on our seats on the stage. Two such carriages are attached to each other by means of a short iron bar, and two horses were hitched up, which do not pull from the front, however, but from the side of the wagon beside the track. We sat a long time waiting for the train of coal cars. Finally we heard, “They’re coming. We hear them.” And soon we really heard a distant sound of rolling wheels and also saw the black train approaching in the distance. As mentioned, there are always fifteen cars attached to each other by means of short iron bars. The cars are made of strong beams and planks, and each one can hold [——] bushels of coal.M37A bushel of corn is 56 lbs., a bushel of wheat 60 lbs., oats 30 to 36 lbs., barley about 43 lbs. A man sits on one of the cars, about in the middle of the column, and holds a chain in his hand with which he reduces the speed; [Page 1:86]at less steep places, [he] doesn’t impede it at all. Four to five hundred paces after the first train of cars, the second one follows, then the third one, equally distant. And now seven wagons with feeding troughs and short bridges for entering, in each of which four mules stand very calmly with their heads forward. The seven

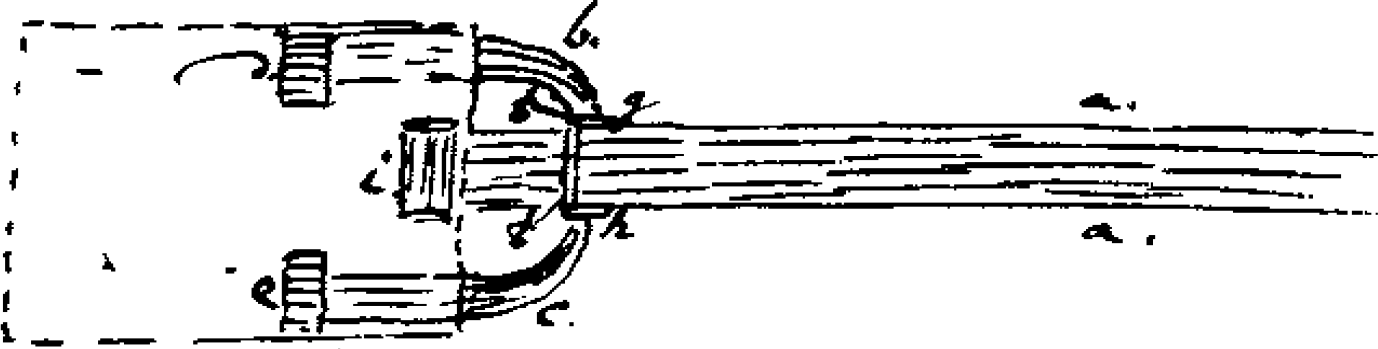

a horn (post horn), in order to give signals. With his other hand he grips a rod. As soon as he pulls back on it, the rod firmly presses a certain wooden device against the wheel, whereby the friction becomes so strong that the wagon is first slowed down and finally, if so desired, brought to a stop. Since the coal cars, expected at any moment from the mines, could not be long in arriving, we had to wait half an hour longer, for one must avoid meeting them on the track, and one always knows the times when the track is free. We sat on our seats on the stage. Two such carriages are attached to each other by means of a short iron bar, and two horses were hitched up, which do not pull from the front, however, but from the side of the wagon beside the track. We sat a long time waiting for the train of coal cars. Finally we heard, “They’re coming. We hear them.” And soon we really heard a distant sound of rolling wheels and also saw the black train approaching in the distance. As mentioned, there are always fifteen cars attached to each other by means of short iron bars. The cars are made of strong beams and planks, and each one can hold [——] bushels of coal.M37A bushel of corn is 56 lbs., a bushel of wheat 60 lbs., oats 30 to 36 lbs., barley about 43 lbs. A man sits on one of the cars, about in the middle of the column, and holds a chain in his hand with which he reduces the speed; [Page 1:86]at less steep places, [he] doesn’t impede it at all. Four to five hundred paces after the first train of cars, the second one follows, then the third one, equally distant. And now seven wagons with feeding troughs and short bridges for entering, in each of which four mules stand very calmly with their heads forward. The seven ![Fig. 3.11. Coal car: “‘a’ [is] the pole with which the wagon is halted. When it is pulled toward ‘b,’ it presses both wooden blocks ‘c’ [and] ‘c’ against the wheel[s], and the friction arrests movement. ‘d’ is a short iron shaft with which the rear wagon is attached to the one in front of it.”](../../../sites/default/files/figures/figure03-11.png) wagons are attached to each other. A man sitting on the coach box controls them, and in this way the traveling troop of twenty-eight mules comes rolling down as swiftly as an arrow.

wagons are attached to each other. A man sitting on the coach box controls them, and in this way the traveling troop of twenty-eight mules comes rolling down as swiftly as an arrow.

The wheels are made of iron. A car like this [carries] 2 tons of coal. Forty-five cars carrying 90 tons of coal travel each time, and this, five times daily, amounts to 450 tons or 25,200 bushels of coal a day.

It made a strange impression when the cars and the mule-troop train approached closer and closer and rolled past extremely rapidly. As soon as it was gone, our grays started out briskly, and we traveled upward at a fast trot, something that can be accomplished only on rails. The railroad continues to follow the forest high mountain wall through woodland, and on the side of the road, one reaches isolated habitations made of hemlock. Cattle grazed nearby. Here one always puts large bells on them so that they can be found again. The valley to our left afforded a wild romantic view. High extensive mountains enclose it every where; forest uniformly covers it from the floor of the valley to the peak; indeed, even in the valley there is a tall, ancient hemlock forest, often intermingled with various kinds of deciduous trees. Deep below flows Mauch Chunk Creek, the name of which comes from the Indians. Beside the road one sees wild grapevines picturesquely and densely overspreading the thickets, as well as various previously mentioned plants, and every mile is indicated there on a white board nailed to  a tree.

a tree.

At midpoint we stopped to wait for cars assumed to be approaching. Some of the group, however, preferred to continue on foot to the collieries immediately. The heat was unusually intense, so that we suffered not a little. Having arrived on the summit, we immediately came upon Mr. Holland’s inn, where we cooled off and had some refreshments. We at once viewed the white-tailed deer he keeps in a small enclosure. There were six of them, including a powerful buck. This buck was particularly splendid with unusually proud bearing. He was large, his neck long and very thick. When he stood still, he carried his head very high and proudly, and when he trotted, he held his scut (tail) straight up; this tail, which was red above and white underneath, was so long and thickly covered with hair that it almost resembled a fox’s tail. The antlers were covered with velvet, which is not frayed until fall. These bucks cast off their antlers in winter, around Christmas, I was told. The fawns still have a few white spots at the end of August.

As soon as we had rested somewhat, we again boarded the stages and, without horses, traveled, following down the slight slope of the railroad to the colliery, about ten minutes from the inn. One reaches these interesting mines near a deep excavation of the upper sandstone layer and then enters the pits, which—perhaps 300 paces long, 150 paces wide, about 30 feet deep, and completely open and clear on top—have gradually expanded to this extent. One hundred and twelve men [Page 1:87]work in these mines, and 130 mules are used to transport the coal. One sees the coal, glistening and gleaming, of better quality in some places than in others, as some of it is dislodged with [gun]powder, some with crowbars, broken up with pickaxes, and scooped into coal cars (wagons). In the mine itself, narrow tracks lead from one part of the pit to the other and outwards, and on them run small rail cars on a few four wheels (like the mine trucks in our German mines), with which a man removes the rubble and refuse. All around the pit, high heaps of this rubble have collected; like promontories, [the heaps] are extended farther and farther outward.

In some places there are impressions of prehistoric plants, perhaps palms and ferns, among which we found some interesting specimens. [For] information on the occurrence of the types of rock accompanying these coal strata see the following note:

Shell-like bright coal (anthracite). The very important deposit of this is located, as far as is known at present, only in the state of Pennsylvania in two sections, not far apart, between the so-called Sharp Mountain, approximately 10 miles northwest of the Blue Mountains, and the Susquehanna River. One section includes the mountains and valleys that extend along the Susquehanna River in the direction from northeast to southwest from the Wyoming River to the large Mahoning River. The width is said to be from 3 to 5 English miles and the length between 60 and 70 miles. The other one includes Sharp Mountain (but only on the northwestern side), the valley between it and the Breiten Berg (Broad Mountain), and, as it seems, the entire Broad Mountain, from which the brooks arise that form the rivers Swatara, Schuylkill, and Lehigh. Of these rivers the latter two empty into the Delaware, but the former, after many bends, into the Susquehanna near Middletown. This section is doubtless 60 to 70 miles long and 3 to 10 miles wide.

Although the anthracite from the last-named section appears to be purer and better than that of the former, neither kind contains any bitumen. In both sections the deposit is part of the independent coal formation. It consists of many beds of coal, separate from and independent of one another, which are from 1 to 30 feet thick. All have the same range, running from northeast to southwest, some toward the south and some descending toward the north, mostly at an angle of 40 to 55 degrees. But there is no absolute law in this respect, because at Mauch Chunk, as well as in the northwest branch of the large Schuylkill, there are deposits with a 6-degree angle, and in the large Schuylkill Valley, completely vertical beds are found. The rock strata that accompany this formation are 1) a conglomerate consisting of rolled pebbles cemented with silica and clay, 2) a peculiar coarse-grained sandstone in which dendrite-shaped manganese infiltrations appear, and 3) a kind of clay in the form of top and bottom strata in which plant impressions of the fern family occur. In the sandstone just mentioned, there are also impressions of palm leaves and cubical pyrites, which produce a lavalike appearance through the disintegration of the rock. The almost horizontal beds always lack the upper stratum, and this is replaced by dustlike coal, in which small lenticular pieces of coal appear. These descend, become larger, and finally merge with the entire mass of coal. This relationship occurs less in the case of those beds that descend at an angle of 40° to 60°.

The iron ores that accompany this formation are 1) bog ore (hydrated iron), 2) Wernerian brown ironstone, 3) stalactite ore, [and] 4) large kidney-shaped argillaceous ironstone with a diameter of 1 inch to 2 feet. Yet the strata are not significant, usually from 6 to 14 inches. To be sure, they share a similar range with the coal deposits but diverge and hence are to be regarded more as pockets. Until now limestone has not been discovered in the formation. This phenomenon especially distinguishes this formation from the bituminous coal formation beyond the Alleghenies, a formation that does, to be sure, include the same types of rock, but where everything is of a finer grain in layers of 6 feet at the most, but above all is characterized by the presence of limestone.

Bituminous coal also contains far more pyrites, from which it cannot possibly be separated by coking and therefore is useless for smelting iron ore. For most purposes the difficulty of burning anthracite coal has already been overcome by most businesses. It has been adapted for smelting cast iron into wrought iron, for breweries, [for] steamships, for heating rooms in open fireplaces as well as in stoves, and for all kitchen uses. The principle that it burns only with a powerful draft of air has been amply refuted, because in the mines, as well as on the canal boats, it is ignited without any draft of air. Its use has increased year by year; indeed, for this year it surpasses 300,000 tons, whereas in the year 1825 it amounted to barely 40,000 tons. Until now hydrocarbon was discovered in only two mines, and thus it appears that at a certain depth, the same condition obtains, as is the case with the bituminous formation.

It costs 75 cents to bring a ton of coal out of the mines. The leaseholders pay 20 to 25 cents per ton, and yet it is never sold in Philadelphia for less than 4 and a half to 5 dollars and in New York for less than 8 dollars. Last winter a ton cost 16 dollars in New York. Bituminous coal imported from Liverpool fetches the same prices, whereas in Pittsburgh bituminous coal sells for two and one-half cents per bushel. Twenty-four bushels are a ton.

Dr. Saynisch took great pains to find good samples of local fossils for me. He has long had a most thorough knowledge of this region, since he is a mineralogist.M38The mines are located at an altitude of 1,460 feet. We returned to the inn, laden with the most beautiful anthracite and samples of other kinds of rock.

The heat on this road was the most intense I had yet endured in North America, and everywhere our judgment was confirmed. Not a breeze was stirring, and [Page 1:88]in the inn the Fahrenheit thermometer registered 98° [36.7°C] at twelve o’clock. We boarded the stage again to ride down to Mauch Chunk. We did not need horses now, but instead the driver pushed the wagon forward a few feet, swung himself onto his seat, and the journey continued, faster than a horse can run at its swiftest gallop. In a period of seventeen minutes, we covered a large part of the distance without stopping. Then we had to halt to let the returning coal cars pass. This probably took twenty minutes. Then the wagon continued so rapidly that we covered the 8 miles from the inn in thirty-two minutes. We now went to see the place where the coal cars were unloaded.

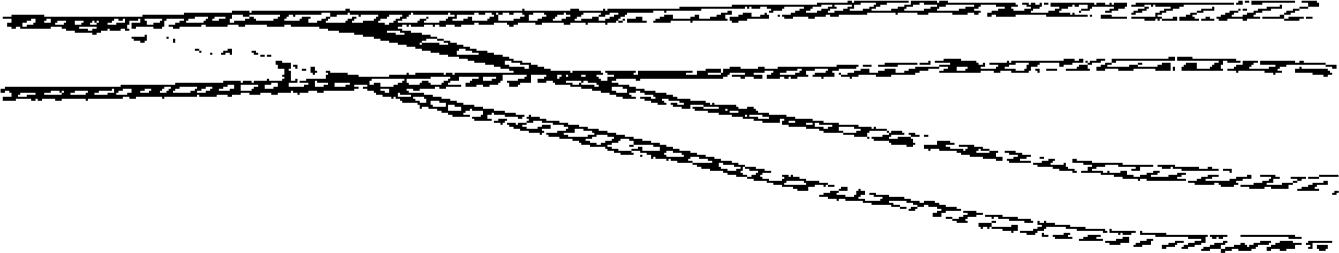

At the end of the railroad on the summit, there is a building equipped with a large winch with a continuous cable. With one end of the cable, a car is lowered on an inclined track, while with the other end, an empty car is drawn up from below. M39It is at least 15 feet in diameter. ![Fig. 3.13. Schematic drawing of Mauch Chunk coal railway delivery system: “‘a’ is the railroad coming from the mines; it goes into the square building, ‘b.’ Inside it at ‘c’ there are four round movable disks in the floor; the car moves onto them. Once it is on them, the disk is turned until the front part of the car faces the iron tracks ‘e–e’ that lead down the mountain to the building ‘g–g,’ which has been constructed at the Lecha. The barge, ‘h,’ is tied up in readiness, and the cars, ‘ f,’ are emptied as soon as they arrive below and [at] ‘ff’ again run up the track. [At] ‘d’ is the winch over which the cables run.”](../../../sites/default/files/figures/figure03-13.png) This machinery is simple and very pleasing to watch. The distance from the building ‘g’ to the house ‘b’ amounts to more than 700 feet.M40In ‘i’ of the lower track, there is a gate where the two tracks intersect and then diverge again.

This machinery is simple and very pleasing to watch. The distance from the building ‘g’ to the house ‘b’ amounts to more than 700 feet.M40In ‘i’ of the lower track, there is a gate where the two tracks intersect and then diverge again.

We went to see a remarkable natural history specimen at Mauch Chunk. In the store there was a stuffed bull elk (Cervus canadensis) that had wounded its keeper or, I believe, several persons, and nearly killed them. It was shot and mounted. It had the size of a large European stag suitable for hunting and also had the shape and virtually all the coloration of our red deer stag in rut, with no black marks on its belly and throat. Its antlers were strong and had 14 points. Moths had badly damaged the proud animal, and if the owner had been present, I would have ventured to assail him with requests for the skull with the antlers.

During the afternoon of this terribly hot day, a severe thunderstorm occurred.[Page 1:89] [It] brought only a little rain to Mauch Chunk but was much heavier farther down in the Lecha Valley, for we found large puddles everywhere and all streams running high. At about six o’clock, we left Mauch Chunk, after we had also inspected a very well built sawmill, the entire mechanism of which had been constructed by a very experienced and skillful major owner of the coal mines, Mr. White, a  Quaker. [See for position of lettered features:] ‘a’ millrace with a 14-foot drop; ‘b’ side canal for the perpendicular paddle wheel, ‘d,’ on whose paddles the water acts at a right angle and whose force is designed to pull the block, which has been cut through once, back again; ‘c,’ canal opposite the preceding one, which turns the perpendicular wheel ‘e,’ whose force is designed to draw the blocks upward. The canal stream, ‘a,’ falls on a long horizontal treble wheel, ‘i,’ whose lateral disks are at most 3 feet in diameter and provided with a crank (rocker?) that moves the saw up and down. The small vertical diameter of the cylinder (‘i’) is the cause of the extraordinarily rapid movement of the saw. As soon as the front sluice gate ‘f–f ’ of the canal (‘a’) is opened, the water drives the horizontal treble wheel, ‘i,’ and the block or trunk put in place in the upper floor of the building is cut through one time. When this has been done, the gate, ‘f–f,’ is closed and the one at ‘g’ is opened, which brings the block back. The gate [at] ‘h’ is opened only when one wants to place a new block before the saw. On the wheel [marked as] ‘e,’ a windlass is placed on which a long chain is attached; this is pulled down by the windlass, and with its first link, a sharp hook, driven down into the block, lifts [the block] up. With this device a worker is able to saw 4,000 square feet of pine wood in twelve hours.

Quaker. [See for position of lettered features:] ‘a’ millrace with a 14-foot drop; ‘b’ side canal for the perpendicular paddle wheel, ‘d,’ on whose paddles the water acts at a right angle and whose force is designed to pull the block, which has been cut through once, back again; ‘c,’ canal opposite the preceding one, which turns the perpendicular wheel ‘e,’ whose force is designed to draw the blocks upward. The canal stream, ‘a,’ falls on a long horizontal treble wheel, ‘i,’ whose lateral disks are at most 3 feet in diameter and provided with a crank (rocker?) that moves the saw up and down. The small vertical diameter of the cylinder (‘i’) is the cause of the extraordinarily rapid movement of the saw. As soon as the front sluice gate ‘f–f ’ of the canal (‘a’) is opened, the water drives the horizontal treble wheel, ‘i,’ and the block or trunk put in place in the upper floor of the building is cut through one time. When this has been done, the gate, ‘f–f,’ is closed and the one at ‘g’ is opened, which brings the block back. The gate [at] ‘h’ is opened only when one wants to place a new block before the saw. On the wheel [marked as] ‘e,’ a windlass is placed on which a long chain is attached; this is pulled down by the windlass, and with its first link, a sharp hook, driven down into the block, lifts [the block] up. With this device a worker is able to saw 4,000 square feet of pine wood in twelve hours.

The Mauch Chunk Company needs six of these mills to cut the wood it requires, since the coal is transported in wooden barges from the canal down the Delaware, and the barges are then sold for firewood in Philadelphia.

The road from Mauch Chunk (pronounced “Mautsch-Tschunk”) through the Lecha Valley is extremely attractive and diverse. From the inn we rode for a long time on a somewhat sandy road along the right bank of the river close to the water. Tall trees cover the bank. To our right we first had the mountain, which is steep and wooded, where Rubus odoratus and other known plants grow, often very picturesquely, in the wild rocks. Finally the mountains recede; fields, meadows, and single dwellings appear to the right in place of the wild wooded mountain.

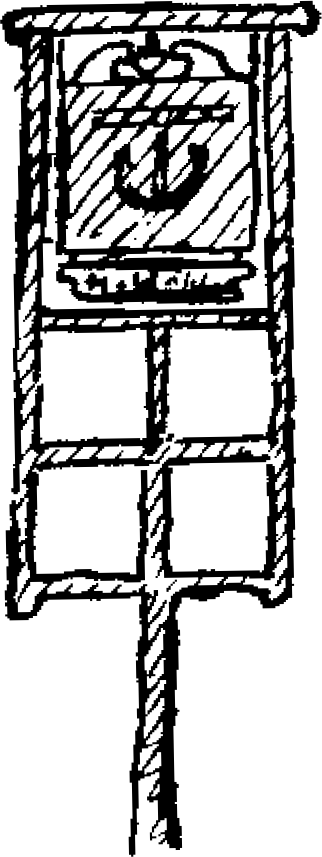

We reached the village Lehighton, where there is an inn whose signboard was visible from a distance. The inns here in the countryside do not have a signboard hanging outside but use instead a tall tree, out in the open, on which a decorated rectangular signboard with a painting and the name of the innkeeper has been mounted, as the adjoining sketch [fig. 3.15] shows. These signboards  are located in front of the house, usually at one corner, and are so tall and large that one can see them from far away. The town Lehighton is located very close to the mouth of the Mahoning Valley (in which the Mahoning Creek flows), a wooded valley with various kinds of settlements. [There] the [Moravian] Brethren in 1769 founded a small settlement that bore the name Gnadenhütten. The Indians later attacked this town, burned down the houses, and murdered [Page 1:90]ten to twelve of the Brethren.M41In his history of Indian missions (pp. 415 and 416), Loskiel provides the following information about this occurrence. On 24 November 1755, in the evening, hostile Indians attacked and burned the communal, or pilgrim, house of the Indian missionaries in Gnadenhütten on the Mahoning. Eleven persons lost their lives, nine of them in the flames. One of the Brethren was shot, another one cruelly slaughtered and then scalped. Three brethren and a sister (the wife of one of them) and a boy escaped and, indeed, the woman and the boy by a lucky leap from the burning roof. One of those who escaped, the missionary Sensemann, who had gone out through the back door right at the onset of the attack to find out why the dogs were barking so loudly, and then found the way back to the others had been cut off, naturally, experienced the agony of seeing his wife perish in the flames. Even now one can see underneath bushes the gravestone that bears their names. The congregation at Gnadenhütten was not reestablished, but there are still individual farmers living on the land that belongs to the Brethren. A strange person, apparently of a higher class and very well educated, lives there now. She came from Germany and, people say, from the Lippe region. Now she devotes herself fully to agriculture, does all the manual labor herself, milks the cows, etc., and has given names to all her domestic animals and tamed them. She has leased some land from the Brethren. Mr. von Schweinitz, as head of the church council, is the principal director.

are located in front of the house, usually at one corner, and are so tall and large that one can see them from far away. The town Lehighton is located very close to the mouth of the Mahoning Valley (in which the Mahoning Creek flows), a wooded valley with various kinds of settlements. [There] the [Moravian] Brethren in 1769 founded a small settlement that bore the name Gnadenhütten. The Indians later attacked this town, burned down the houses, and murdered [Page 1:90]ten to twelve of the Brethren.M41In his history of Indian missions (pp. 415 and 416), Loskiel provides the following information about this occurrence. On 24 November 1755, in the evening, hostile Indians attacked and burned the communal, or pilgrim, house of the Indian missionaries in Gnadenhütten on the Mahoning. Eleven persons lost their lives, nine of them in the flames. One of the Brethren was shot, another one cruelly slaughtered and then scalped. Three brethren and a sister (the wife of one of them) and a boy escaped and, indeed, the woman and the boy by a lucky leap from the burning roof. One of those who escaped, the missionary Sensemann, who had gone out through the back door right at the onset of the attack to find out why the dogs were barking so loudly, and then found the way back to the others had been cut off, naturally, experienced the agony of seeing his wife perish in the flames. Even now one can see underneath bushes the gravestone that bears their names. The congregation at Gnadenhütten was not reestablished, but there are still individual farmers living on the land that belongs to the Brethren. A strange person, apparently of a higher class and very well educated, lives there now. She came from Germany and, people say, from the Lippe region. Now she devotes herself fully to agriculture, does all the manual labor herself, milks the cows, etc., and has given names to all her domestic animals and tamed them. She has leased some land from the Brethren. Mr. von Schweinitz, as head of the church council, is the principal director.

Near the outlet of the Mahoning Valley a wooden bridge has been very picturesquely constructed over the Lecha. Its foundations have been blasted rather high up, and tall, picturesque timber surrounds this scene on all sides, while to the right, one discerns the high forested mountains of the Mahoning Valley peeking out over it. Work is now being done on the bridge, so that we had to travel down on the other side of it through dense, shady trees to the river and cross it, whereby the high stones, jutting out of the rubble and hidden because of the cloudiness of the water, could easily have overturned the wagon. From here we reached a level open place in the valley where there are several scattered dwellings known as Weissport. A certain Weiss wanted to found a city here; for this purpose he had collected several people signatures, but at present the “city” consists of three or four houses. Not far beyond these dwellings, the Pohopoco Creek was heavily swollen because of the rain.

One crosses a bridge and near a nice house, recently rebuilt after a fire, reaches the side of the valley, where the road has been laid along the mountain, elevated above the water. This road, without a railing, is not the safest, especially at night or if one has shy horses. A small wooded ravine to the left is called the Fireline because, as people say, during the destruction of Gnadenhütten, troops hastening to its aid saw the fire in the Mahoning Valley from there. We continued driving along the side of the mountain through wild forest, part of the way on a new, recently relocated road, past several habitations, and [then] night fell. In the mountain to our right, the Blue Mountain, the moon revealed to us a deep cleft, the so-called Lecha or Lehigh Gap, the opening where this river cuts through the mountains, and that is where the inn is located in which we wished to spend the night. By means of a long detour, we reached that place and found very good lodgings. The landlord spoke German and English; he was the son of the late General Craig, who is said to have distinguished himself on several occasions.